Table of Contents

I’ve been continuously following the computer vision (CV) and image synthesis research scene at Arxiv and elsewhere for around five years, so trends become evident over time, and they shift in new directions every year.

Therefore as 2024 draws to a close, I thought it appropriate to take a look at some new or evolving characteristics in Arxiv submissions in the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition section. These observations, though informed by hundreds of hours studying the scene, are strictly anecdata.

The Ongoing Rise of East Asia

By the end of 2023, I had noticed that the majority of the literature in the ‘voice synthesis’ category was coming out of China and other regions in east Asia. At the end of 2024, I have to observe (anecdotally) that this now applies also to the image and video synthesis research scene.

This does not mean that China and adjacent countries are necessarily always outputting the best work (indeed, there is some evidence to the contrary); nor does it take account of the high likelihood in China (as in the west) that some of the most interesting and powerful new developing systems are proprietary, and excluded from the research literature.

But it does suggest that east Asia is beating the west by volume, in this regard. What that’s worth depends on the extent to which you believe in the viability of Edison-style persistence, which usually proves ineffective in the face of intractable obstacles.

There are many such roadblocks in generative AI, and it is not easy to know which can be solved by addressing existing architectures, and which will need to be reconsidered from zero.

Though researchers from east Asia seem to be producing a greater number of computer vision papers, I have noticed an increase in the frequency of ‘Frankenstein’-style projects – initiatives that constitute a melding of prior works, while adding limited architectural novelty (or possibly just a different type of data).

This year a far higher number of east Asian (primarily Chinese or Chinese-involved collaborations) entries seemed to be quota-driven rather than merit-driven, significantly increasing the signal-to-noise ratio in an already over-subscribed field.

At the same time, a greater number of east Asian papers have also engaged my attention and admiration in 2024. So if this is all a numbers game, it’s not failing – but neither is it cheap.

Increasing Volume of Submissions

The volume of papers, across all originating countries, has evidently increased in 2024.

The most popular publication day shifts throughout the year; at the moment it is Tuesday, when the number of submissions to the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition section is often around 300-350 in a single day, in the ‘peak’ periods (May-August and October-December, i.e., conference season and ‘annual quota deadline’ season, respectively).

Beyond my own experience, Arxiv itself reports a record number of submissions in October of 2024, with 6000 total new submissions, and the Computer Vision section the second-most submitted section after Machine Learning.

However, since the Machine Learning section at Arxiv is often used as an ‘additional’ or aggregated super-category, this argues for Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition actually being the most-submitted Arxiv category.

Arxiv’s own statistics certainly depict computer science as the clear leader in submissions:

Computer Science (CS) dominates submission statistics at Arxiv over the last five years. Source: https://info.arxiv.org/about/reports/submission_category_by_year.html

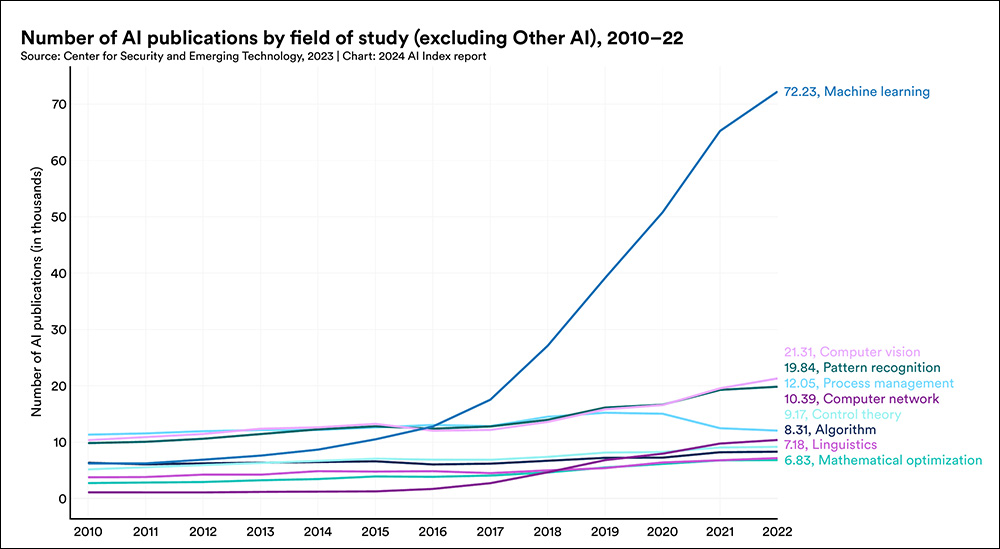

Stanford University’s 2024 AI Index, though not able to report on most recent statistics yet, also emphasizes the notable rise in submissions of academic papers around machine learning in recent years:

With figures not available for 2024, Stanford’s report nonetheless dramatically shows the rise of submission volumes for machine learning papers. Source: https://aiindex.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/HAI_AI-Index-Report-2024_Chapter1.pdf

Diffusion>Mesh Frameworks Proliferate

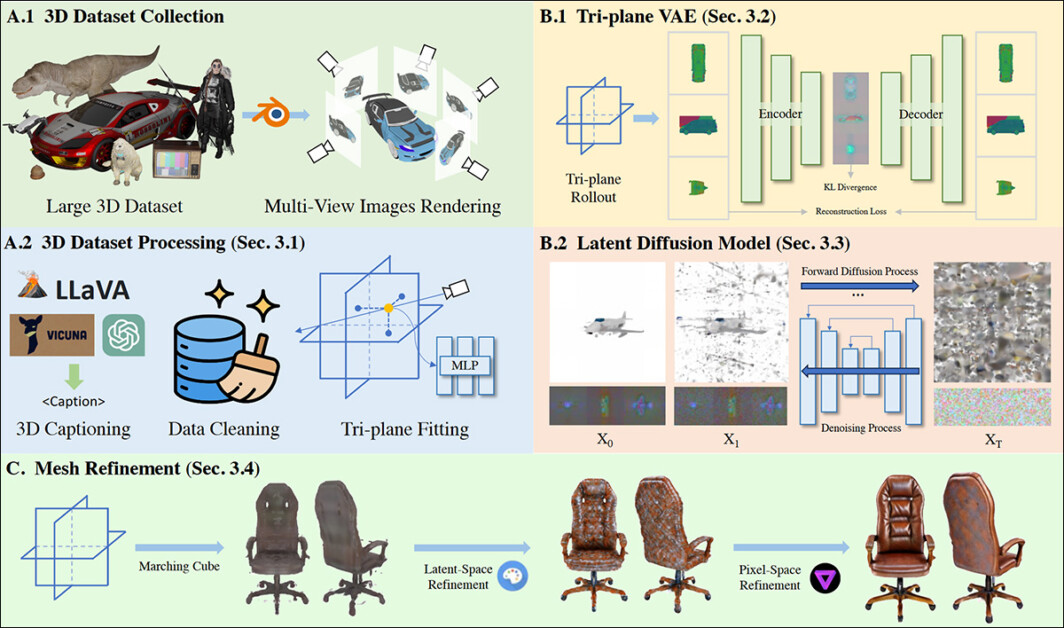

One other clear trend that emerged for me was a large upswing in papers that deal with leveraging Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs) as generators of mesh-based, ‘traditional’ CGI models.

Projects of this type include Tencent’s InstantMesh3D, 3Dtopia, Diffusion2, V3D, MVEdit, and GIMDiffusion, among a plenitude of similar offerings.

Mesh generation and refinement via a Diffusion-based process in 3Dtopia. Source: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2403.02234

This emergent research strand could be taken as a tacit concession to the ongoing intractability of generative systems such as diffusion models, which only two years were being touted as a potential substitute for all the systems that diffusion>mesh models are now seeking to populate; relegating diffusion to the role of a tool in technologies and workflows that date back thirty or more years.

Stability.ai, originators of the open source Stable Diffusion model, have just released Stable Zero123, which can, among other things, use a Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) interpretation of an AI-generated image as a bridge to create an explicit, mesh-based CGI model that can be used in CGI arenas such as Unity, in video-games, augmented reality, and in other platforms that require explicit 3D coordinates, as opposed to the implicit (hidden) coordinates of continuous functions.

Click to play. Images generated in Stable Diffusion can be converted to rational CGI meshes. Here we see the result of an image>CGI workflow using Stable Zero 123. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RxsssDD48Xc

3D Semantics

The generative AI space makes a distinction between 2D and 3D systems implementations of vision and generative systems. For instance, facial landmarking frameworks, though representing 3D objects (faces) in all cases, do not all necessarily calculate addressable 3D coordinates.

The popular FANAlign system, widely used in 2017-era deepfake architectures (among others), can accommodate both these approaches:

Above, 2D landmarks are generated based solely on recognized face lineaments and features. Below, they are rationalized into 3D X/Y/Z space. Source: https://github.com/1adrianb/face-alignment

So, just as ‘deepfake’ has become an ambiguous and hijacked term, ‘3D’ has likewise become a confusing term in computer vision research.

For consumers, it has typically signified stereo-enabled media (such as movies where the viewer has to wear special glasses); for visual effects practitioners and modelers, it provides the distinction between 2D artwork (such as conceptual sketches) and mesh-based models that can be manipulated in a ‘3D program’ like Maya or Cinema4D.

But in computer vision, it simply means that a Cartesian coordinate system exists somewhere in the latent space of the model – not that it can necessarily be addressed or directly manipulated by a user; at least, not without third-party interpretative CGI-based systems such as 3DMM or FLAME.

Therefore the notion of diffusion>3D is inexact; not only can any type of image (including a real photo) be used as input to produce a generative CGI model, but the less ambiguous term ‘mesh’ is more appropriate.

However, to compound the ambiguity, diffusion is needed to interpret the source photo into a mesh, in the majority of emerging projects. So a better description might be image-to-mesh, while image>diffusion>mesh is an even more accurate description.

But that’s a hard sell at a board meeting, or in a publicity release designed to engage investors.

Evidence of Architectural Stalemates

Even compared to 2023, the last 12 months’ crop of papers exhibits a growing desperation around removing the hard practical limits on diffusion-based generation.

The key stumbling block remains the generation of narratively and temporally consistent video, and maintaining a consistent appearance of characters and objects – not only across different video clips, but even across the short runtime of a single generated video clip.

The last epochal innovation in diffusion-based synthesis was the advent of LoRA in 2022. While newer systems such as Flux have improved on some of the outlier problems, such as Stable Diffusion’s former inability to reproduce text content inside a generated image, and overall image quality has improved, the majority of papers I studied in 2024 were essentially just moving the food around on the plate.

These stalemates have occurred before, with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and with Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF), both of which failed to live up to their apparent initial potential – and both of which are increasingly being leveraged in more conventional systems (such as the use of NeRF in Stable Zero 123, see above). This also appears to be happening with diffusion models.

Gaussian Splatting Research Pivots

It seemed at the end of 2023 that the rasterization method 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS), which debuted as a medical imaging technique in the early 1990s, was set to suddenly overtake autoencoder-based systems of human image synthesis challenges (such as facial simulation and recreation, as well as identity transfer).

The 2023 ASH paper promised full-body 3DGS humans, while Gaussian Avatars offered massively improved detail (compared to autoencoder and other competing methods), together with impressive cross-reenactment.

This year, however, has been relatively short on any such breakthrough moments for 3DGS human synthesis; most of the papers that tackled the problem were either derivative of the above works, or failed to exceed their capabilities.

Instead, the emphasis on 3DGS has been in improving its fundamental architectural feasibility, leading to a rash of papers that offer improved 3DGS exterior environments. Particular attention has been paid to Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) 3DGS approaches, in projects such as Gaussian Splatting SLAM, Splat-SLAM, Gaussian-SLAM, DROID-Splat, among many others.

Those projects that did attempt to continue or extend splat-based human synthesis included MIGS, GEM, EVA, OccFusion, FAGhead, HumanSplat, GGHead, HGM, and Topo4D. Though there are others besides, none of these outings matched the initial impact of the papers that emerged in late 2023.

The ‘Weinstein Era’ of Test Samples Is in (Slow) Decline

Research from south east Asia in general (and China in particular) often features test examples that are problematic to republish in a review article, because they feature material that is a little ‘spicy’.

Whether this is because research scientists in that part of the world are seeking to garner attention for their output is up for debate; but for the last 18 months, an increasing number of papers around generative AI (image and/or video) have defaulted to using young and scantily-clad women and girls in project examples. Borderline NSFW examples of this include UniAnimate, ControlNext, and even very ‘dry’ papers such as Evaluating Motion Consistency by Fréchet Video Motion Distance (FVMD).

This follows the general trends of subreddits and other communities that have gathered around Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs), where Rule 34 remains very much in evidence.

Celebrity Face-Off

This type of inappropriate example overlaps with the growing recognition that AI processes should not arbitrarily exploit celebrity likenesses – particularly in studies that uncritically use examples featuring attractive celebrities, often female, and place them in questionable contexts.

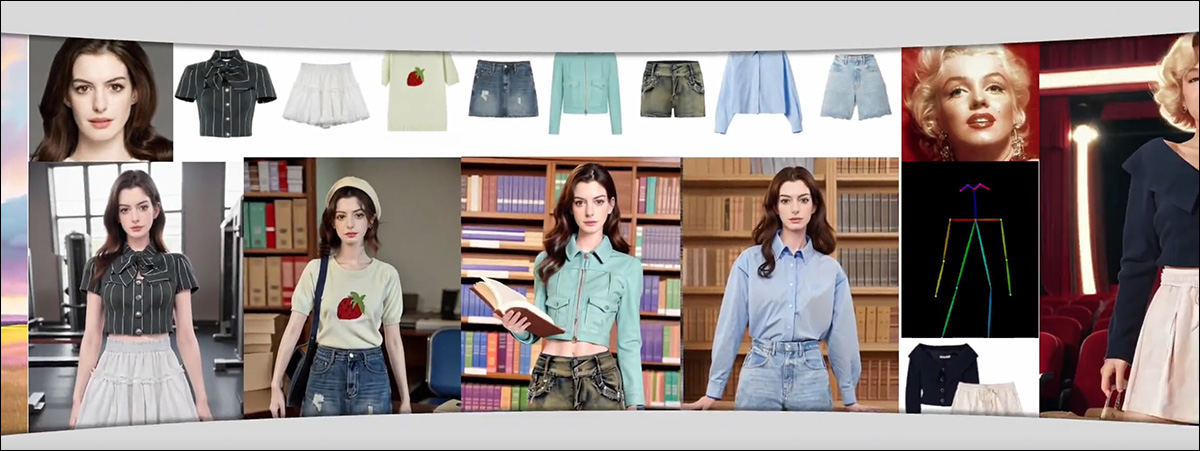

One example is AnyDressing, which, besides featuring very young anime-style female characters, also liberally uses the identities of classic celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe, and current ones such as Ann Hathaway (who has denounced this kind of usage quite vocally).

Arbitrary use of current and ‘classic’ celebrities is still fairly common in papers from south east Asia, though the practice is slightly on the decline. Source: https://crayon-shinchan.github.io/AnyDressing/

In western papers, this particular practice has been notably in decline throughout 2024, led by the larger releases from FAANG and other high-level research bodies such as OpenAI. Critically aware of the potential for future litigation, these major corporate players seem increasingly unwilling to represent even fictional photorealistic people.

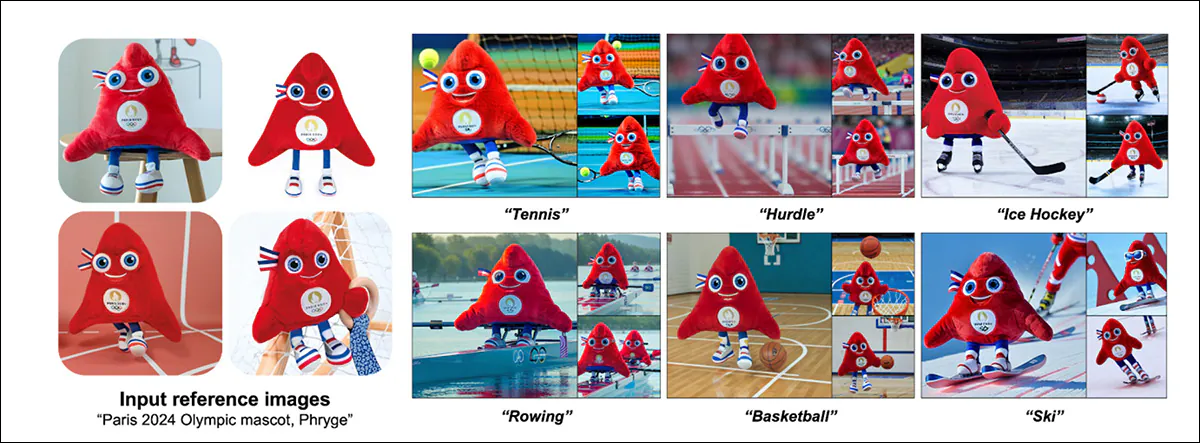

Though the systems they are creating (such as Imagen and Veo2) are clearly capable of such output, examples from western generative AI projects now trend towards ‘cute’, Disneyfied and extremely ‘safe’ images and videos.

Despite vaunting Imagen’s capacity to create ‘photorealistic’ output, the samples promoted by Google Research are typically fantastical, ‘family’ fare – photorealistic humans are carefully avoided, or minimal examples provided. Source: https://imagen.research.google/

Face-Washing

In the western CV literature, this disingenuous approach is particularly in evidence for customization systems – methods which are capable of creating consistent likenesses of a particular person across multiple examples (i.e., like LoRA and the older DreamBooth).

Examples include orthogonal visual embedding, LoRA-Composer, Google’s InstructBooth, and a multitude more.

Google’s InstructBooth turns the cuteness factor up to 11, even though history suggests that users are more interested in creating photoreal humans than furry or fluffy characters. Source: https://sites.google.com/view/instructbooth

However, the rise of the ‘cute example’ is seen in other CV and synthesis research strands, in projects such as Comp4D, V3D, DesignEdit, UniEdit, FaceChain (which concedes to more realistic user expectations on its GitHub page), and DPG-T2I, among many others.

The ease with which such systems (such as LoRAs) can be created by home users with relatively modest hardware has led to an explosion of freely-downloadable celebrity models at the civit.ai domain and community. Such illicit usage remains possible through the open sourcing of architectures such as Stable Diffusion and Flux.

Though it is often possible to punch through the safety features of generative text-to-image (T2I) and text-to-video (T2V) systems to produce material banned by a platform’s terms of use, the gap between the restricted capabilities of the best systems (such as RunwayML and Sora), and the unlimited capabilities of the merely performant systems (such as Stable Video Diffusion, CogVideo and local deployments of Hunyuan), is not really closing, as many believe.

Rather, these proprietary and open-source systems, respectively, threaten to become equally useless: expensive and hyperscale T2V systems may become excessively hamstrung due to fears of litigation, while the lack of licensing infrastructure and dataset oversight in open source systems could lock them entirely out of the market as more stringent regulations take hold.

First published Tuesday, December 24, 2024