U.S. health officials have encountered obstacles in their efforts to determine whether a Missouri person infected with the H5N1 bird flu passed the virus to others, causing a delay that is likely to fuel concerns about the possibility that has been human-to-human transmission.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has blood samples from several health care workers and a household contact from the Missouri case that they want to test for antibodies that would indicate whether they too were infected with the virus, an agency official told STAT.

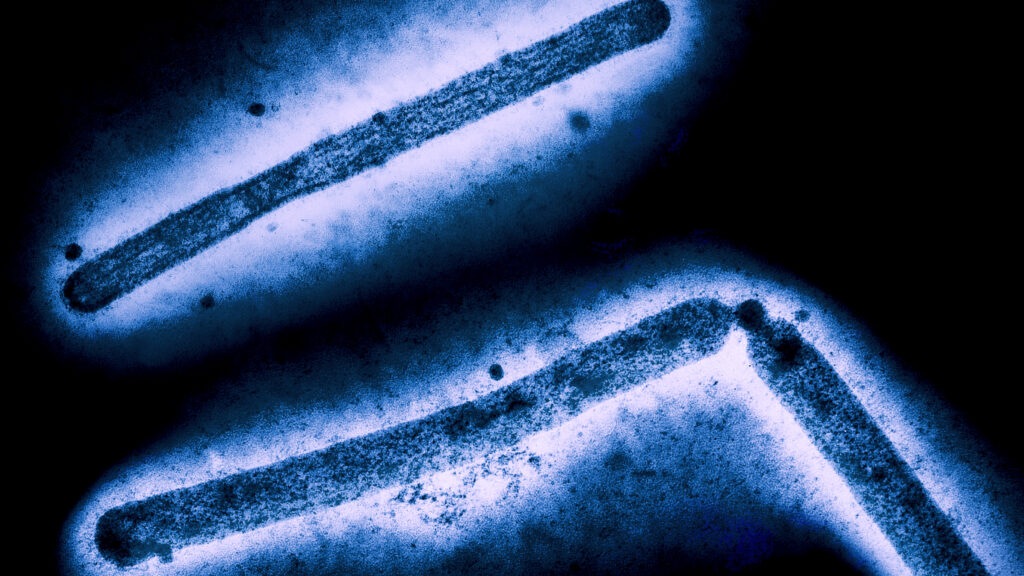

But the CDC has had to develop a new test to look for those antibodies because significant genetic changes to the key protein on the outside of the virus, found in the Missouri case, meant the agency’s existing tests may not have been reliable. said Demetre Daskalakis, director of the CDC’s National Center on Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, in an interview. He suggested it will be mid-October before the work can be completed.

“The antibodies that would grow in the person who was exposed to that virus would then be different than the antibodies that would grow in a person who had a virus without those mutations,” Daskalakis said.

Developing the new test was a challenge because the patient sample contained so little viral material that the CDC was unable to grow entire viruses from it. Instead, the scientists had to reverse engineer H5N1 viruses containing the changes to use them as the basis for the new serological test, he said.

There is still no explanation for how the person contracted the virus. The unidentified person was hospitalized on August 22 for other health problems and was released three days later. While in the hospital, the person was tested for a panel of respiratory viruses and tested positive for influenza.

The state’s ongoing investigation into the case has retroactively identified six health care workers who cared for the patient, who developed respiratory symptoms. One tested negative for flu when he or she was sick, but the other five were not tested while sick. Neither does the household contact. Blood from these six people will be tested for H5N1 antibodies.

There are fears in some quarters that this is a cluster of cases, which infectious disease experts agree would be worrying. Although spread of the virus likely occurred from person to person outside the US, it is primarily an H5N1 virus that cannot easily infect people or spread from one person to another. If that were to change, the risk of a pandemic would be dramatically increased. That possibility has fueled an understandable desire for answers about the Missouri case, and fast.

But that’s not possible in this case, Daskalakis said. “Biology takes time,” he said.

Jesse Bloom, an evolutionary virologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, recently commented on the Missouri virus mutations on the social media site sufficiently important that it could affect the effectiveness of some of the candidate vaccine viruses created as starting materials for H5 vaccines, if mass production is required.

Bloom told STAT that the mutation is not present in the candidate virus used to produce 4.8 million vaccine doses currently held in the Department of Health and Human Services’ national pre-pandemic flu vaccine stockpile.

The mutation in the Missouri virus could also affect a serology test’s ability to detect antibodies in blood samples, if the test doesn’t look for antibodies that recognize it, Bloom said. The result may be a false negative test, or test results that are difficult to read.

“If you get serology that’s at this equivocal level, where it’s a little difficult to be sure if it’s positive or negative, this type of mutation could certainly make you want to retest with a virus that that mutation,” Bloom said.

The CDC is also concerned about the possibility that antibodies against seasonal flu strains — which virtually every living adult would have — could cause a false-positive result when the H5N1 serology test is administered. So the agency’s labs will also take the extra step of depleting each sample of antibodies against H1N1, one of the human flu strains, before testing the Missouri blood samples for H5N1 antibodies, Daskalakis said.

All this work increases the time it takes to arrive at answers. But Bloom viewed it as defensible, although he emphasized that he had no details about the approach the CDC is taking to test the Missouri samples.

“As someone who is very interested, I hope they can do it as soon as possible,” he said. But he noted that in a case like this, “serology can be a little trickier if you’re trying to come to a very confident conclusion.”

“I’m sure they don’t want to prematurely release something that’s inaccurate. So if they don’t get a super clear answer, they might want to spend more time working on positive and negative controls and really making sure they’re right in terms of what they’re ultimately saying,” Bloom said.

Michael Osterholm, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Diseases Research and Policy, also said he can understand the delay, although he expressed concern that some people have already concluded that transmission has occurred in Missouri.

While it is possible that serological tests will show that some of the patient’s contacts are infected, it is also possible that those individuals had Covid-19 or another respiratory infection, he said.

“We’ll all just have to wait and see,” Osterholm said.

Meanwhile, the CDC continues to monitor multiple data streams for indications of unusual flu activity in Missouri, Daskalakis said. To date, there has been nothing to cause alarm.

“We don’t see anything that looks like a flu signal,” he said. “All systems are running at full speed to ensure that we see [it] if something is wrong.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly suggested that the mutation in the Missouri patient’s virus could have eroded the effectiveness of all the H5 vaccines the U.S. government has stockpiled.