People work in groups all the time. In fact, I think it has made us stronger. Specialization and trade allow a team to achieve things that no individual could achieve alone. Economists since Adam Smith have emphasized the group effort required to produce even simple things such as woolen coats, pencilsAnd bread. Liberals have long celebrated the ability of people to work together without explicit coordination!

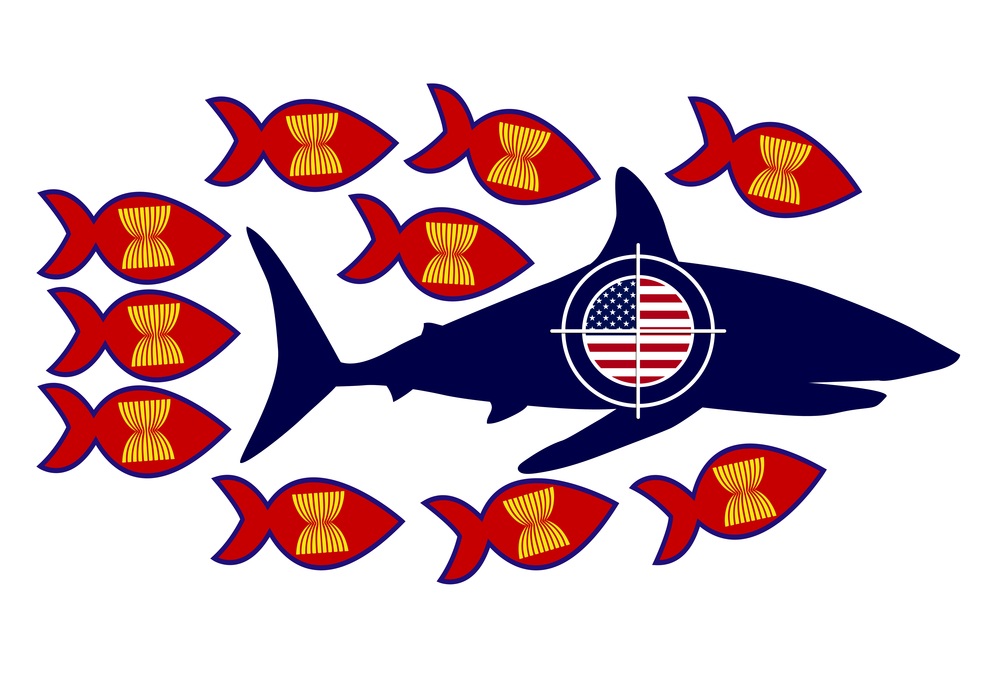

However, these collectives sometimes become intermingled. What is good for one group is often said to be good for another. Or that there is an umbrella group, and that all other groups are included in that group. Again, what is good for that umbrella group is said to be good for all its parts. We see this especially in international trade, and especially in protectionism. Protectionism is full of this misconception about composition, especially the national defense justification for tariffs.

I’ve written a lot about national defense justifications for tariffs. This 2018 piece from me here at Econlog remains one of my favorites. I am working with Don Boudreaux on a book on international trade, in which we delve deeper into the justifications for national defense. The essential idea is that something good is needed for national defense; obtaining it from a foreign source carries a high risk of disruption, which is why tariffs are needed to try to develop the industry domestically.

However, theory often deviates from reality, and there is increasing evidence that national defense tariffs are actually being implemented weaken national defense capabilities (see, for example, those of Colin Grabow and Inu Manak). The Case Against the Jones Act or Mancur Olson’s The economics of wartime deficit).

But the argument for tariffs on military goods, at least in the way they are currently deployed, rests on confusion about collectives. Let’s assume that the national defense rates are:

- Necessary,

- Easily aimed

- Not susceptible to profiteering, political manipulation or other forms of corruption

In short, let’s assume that national defense tariffs work perfectly as intended. However, it does not logically follow that these national defense tariffs would be the best, or even a good, way to achieve the intended goals. Tariffs, recall, applicable to all users of a particular input, not just one. For example, companies that use microchips for their products also have to pay higher prices for their inputs.

The justification for national defense tariffs is presented as “We‘I want a domestic source of good. But that is not the case. The government wants it. But most of us don’t. Why force others to pay a higher price when only one group needs that price? The government can purchase from domestic suppliers. It is not necessary to force everyone to do so.

In other words, we should not view “The United States of America” as a single collective entity represented entirely by the wishes and desires of the federal government, but rather as a collection of different groups, each with their own individual wishes and needs. desires and their own agency. The federal government is not the representative of Americans. It is a unique company with a specific purpose. She may conduct her business as she sees fit. But what is desirable for the government is not necessarily desirable for the people living under the government (and vice versa).

Collectivist ideologies have many problems. One of the biggest is that they ignore the complexity of society by lumping everything under one broad umbrella and conflating it with government. This in turn leads to many disastrous policy mistakes, such as protectionism.

Jon Murphy is an assistant professor of economics at Nicholls State University.