Genetic sequences of H5N1 bird flu viruses collected from a person in Louisiana who became seriously ill show signs of developing several mutations that are thought to affect the virus’s ability to attach to cells in the upper respiratory tract of humans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported on Thursday.

One of the mutations was also seen in a virus sample from a teenager in British Columbia, who was in critical condition in a Vancouver hospital for weeks after contracting H5N1.

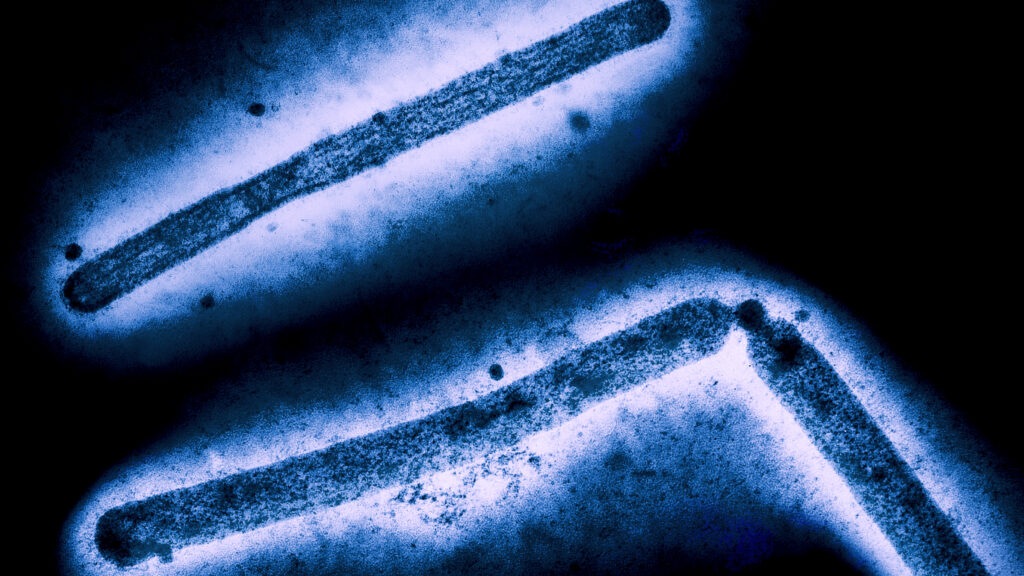

The mutation seen in both viruses is thought to help adapt H5N1 to be able to bind to cell receptors found in the upper respiratory tract of humans. Bird flu viruses normally attach to a type of cell receptor that is rare in the human upper respiratory tract, which is likely one reason why H5N1 does not easily infect humans and does not spread from person to person when it does.

Scott Hensley, a professor of microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, cautioned against reading too much into the data from two serious cases, though he admitted the CDC’s report was “enough to raise my eyebrows.” .”

“It’s not great. It’s not great news,” Hensley told STAT.

The CDC reported that its scientists compared viruses collected from the unidentified Louisiana patient with viruses from infected poultry on the person’s property. The mutations seen in the patient’s samples were not present in the birds’ virus, indicating that the mutations developed during the course of the person’s infection.

“The observed changes were likely caused by replication of this virus in the patient with advanced disease, rather than being primarily transmitted at the time of infection,” the report said.

This is also believed to have been the case with the British Columbia patient, although health officials there had no source virus to investigate because they were never able to determine how the teen became infected.

Hensley said it would have been more worrying if the mutations in the birds’ virus had been observed, as this would have suggested that viruses in nature would adopt these changes.

Angela Rasmussen, a virologist who specializes in emerging infectious diseases, agreed that the news would have been worse if the mutations had been observed in the virus from the Louisiana patient’s poultry. But she called the current H5N1 situation “scary” and noted that there has been an explosion of human cases.

“More [genetic] Sequencing people is a trend we need to reverse – we need fewer infected people, period,” Rasmussen, who works at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Canada, said on the social media site formerly known as Twitter).

“We don’t know what combination of mutations would lead to a pandemic H5N1 virus and there is only so much we can predict from this sequence data. But the more people are infected, the greater the chance that a pandemic virus will emerge.”

There have been at least 65 confirmed cases of H5N1 bird flu in humans in the United States this year, since the ongoing outbreak of H5N1 in dairy cows was first confirmed in late March. About 60% of the cases involved people who became infected after contact with infected cows; most others were infected through contact with infected poultry, either during culling of birds at affected commercial operations or, in the case of the Louisiana individual, through contact with an infected backyard flock. In two cases the source of contamination was not found.

The version of the virus circulating in cows is slightly different from the version found in wild birds and in most outbreaks on poultry farms. The bovine virus is clade 2.3.4.4b genotype B3.13, while the avian version is 2.3.4.4b genotype D1.1 or D1.2.

Both the Louisiana and British Columbia cases were caused by genotype D1.1 viruses. They are the only two serious infections reported in North America in 2024.

The current status of the Louisiana case is unknown. “We are not providing updates on the patient’s condition at this time,” Emma Herrock, communications director for Louisiana’s Department of Health, said via email Thursday.

Hensley said his lab is working to test whether the mutations seen in the British Columbia teen’s virus actually increase binding to human cells, as is believed. He expects to have the results of that work in early January.

Even if they do, it’s not clear that would be enough for the virus to easily infect people and transmit from person to person, he said. It is thought that other changes would be needed in other parts of the virus. “We know that attachment is a prerequisite, but it may not be enough,” he said.

No further transmission had been seen from the British Columbia teen. And Louisiana has found no secondary cases among contacts of the person who was hospitalized.

The CDC said it is working with the Louisiana Department of Public Health to generate genetic sequences from samples taken from the person later in the infection to see if additional mutations have developed.

— Megan Molteni contributed reporting.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the genotype of the H5N1 virus circulating in cows.