For me it was a great idea. Your mileage may vary.

Yesterday, Arnold Kling posted on his Substack about the pitfalls of studying economics. Given its contents, it is aptly titled: “Beware of Econ Grad School.”

Arnold lists 3 possible motives for obtaining a PhD. in economics.

Intellectual curiosity. You like to explore ideas, you want to better understand how the economy works and you want to come up with answers to puzzles and problems in the economic field.

Lifestyle. You want to produce economics papers, you want autonomy, and you want your only professional interactions to be with other economics professors.

Other. For example, you may want a career in policymaking in economics. (bold in original)

If someone had shown me these three motives when I was considering college, and if I had been convinced that these were the only possible motives, I would have decided not to pursue a PhD.

Let’s look at them one by one.

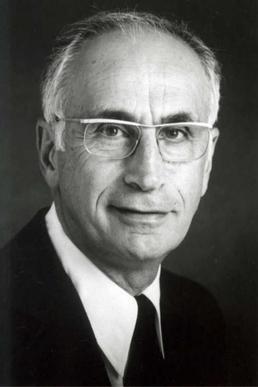

Intellectual curiosity. Of the three, this is the closest for me, even if it’s not very close. I liked the idea of exploring ideas and better understanding how the economy works. But I didn’t think I had the ability to figure out answers to puzzles and problems. The understanding was enough for me, and UCLA delivered in spades. Indeed, it wasn’t until I studied at UCLA with Armen Alchian, Sam Peltzman, Ben Klein, Harold Demsetz, Jack Hirshleifer, and George Hilton, and TAed with Chuck Baird, that I began to think more deeply about puzzles and problems than I ever had done. what I expected when I applied. I learned things I had never wondered about, especially from Alchian and Klein, such as why various activities of companies that are a mystery to someone trained only in perfect competition are consistent with competition, broadly understood. That was all a bonus. And Hirshleifer, Demsetz, Peltzman and Hilton made me think about things I had never thought about before. Finally, Chuck Baird’s TA course for Undergraduate Macroeconomics taught me a lot of macroeconomics. All this learning was a bonus compared to what I expected.

Lifestyle. Initially I had no desire to produce economic articles. I wanted to do that at my first job, at the University of Rochester Graduate School of Management (now the Simon School) from 1975 to 1979. That developed as I read the academic literature and found gaps and also read the popular books . economic literature and came to different conclusions than the one I was reading, written by even the great Milton Friedman. I wanted and have always wanted autonomy. But I never wanted my only professional interactions to be with other economics professors. I had good professional interactions with students, especially graduate students. And I had professional contact with non-professors when, at age 28, I testified twice before congressional committees, once before the House Ways and Means Committee, about a piece I wrote after noticing an error in Milton Friedman’s book. Newsweek column (and the late Lindley Clark wrote an entire column about my testimony in the Wall Street Journal) and once before the Senate Armed Services Committee. I also started doing media work for local TV and radio shows in Rochester. I came in as a professional economist, but of course I had no contact with professional economists.

Other. I never wanted a career in policy making, but I wanted to get a taste of it and I did get a taste of it, first six months at the Ministry of Labor and then two years at the Council of Economic Advisers. When I told Milton Friedman, who called himself my “Dutch uncle,” that I had an opportunity to serve in the Reagan administration, he told me to take it for two years. I went for 2.5 years, which means I followed his advice in my mind.

What has been left out?

Arnold left out three important things that I can think of: (1) teaching, (2) the think tank world, and (3) consulting. I did all three and enjoyed them, but what I enjoyed most was teaching.

When I started graduate school, I was 21. I didn’t know enough or think long term enough to know what I wanted to get out of it or where it would lead. But it was a great step. I admit that one motive I had for completing my PhD, one that would not apply to most readers, is that it would give me a much better chance at a green card.

The way I see it, there are two main strategies for the type of graduate school you should attend. The first is to go to the highest ranked school you can go to, realize that you won’t learn much economics and not find much of what you learn interesting, hold your nose for four years, and then get a job Search for the type of school that suits you. Former co-blogger Bryan Caplan did this at Princeton and then got a great job at George Mason University. The second is to go to a school like George Mason University, where you learn a lot of economics but don’t get as many good opportunities in the job market. But even there the odds can be good. I am reminded of that fact every year when I go to the annual meetings of the Association for Private Enterprise Education and meet at least ten young, interesting economists whom I had never heard of or knew little about, at least five of whom are. received their doctorate from GMU.

The bottom line is that when deciding whether to pursue a Ph.D. In economics, think as hard as you can about who you are, what your interests and abilities are, and what kind of job you want. All this is difficult to imagine when you are young. But don’t limit yourself, as Arnold Kling did, to a subset of possible motives.

Note: The photo above is by Armen Alchian, who has taught me more economics than any other economist. However, many of my UCLA professors have taught me almost as much.