Table of Contents

New Harmony, Indiana

This year is the 200th anniversary of British industrialist Robert Owen’s social experiments at New Harmony, Indiana—a utopian commune on 20,000 acres along the Wabash River near Evansville. Much has been written about Robert Owen and the community at New Harmony. Owen has been described as a forerunner of socialism and the cooperative movement. He is also credited as a founder of utopian socialism. Benjamin Rogge devotes a whole chapter of his classic book, Can Capitalism Survive (Rogge 1979), to the experiments along the Wabash, arguing that their stories offer “three morality tales” for historical guidance. Rogge’s morality tales also illustrate some of the classic economic arguments against socialism—namely, why knowledge and incentive problems cause failure, especially at large scales, and why well-intentioned people find socialism so alluring despite its many failures. For these reasons, Owen’s utopian socialism took just two years to fail at New Harmony. But the story begins a decade beforehand.

Beginnings

The town of Harmony was founded in 1814 by a religious group of German immigrants called the “Harmonists” or “Rappites” (after their leader, George Rapp). As with many 19th-century religious Americans, they believed that the Second Coming of Christ was imminent. For the Harmonists, this manifested as a desire to strive for temporal perfection in communal living, while anticipating His return to govern the Earth. Through Rapp’s leadership and a drive to live in Christian community, their enterprise is widely viewed to have been quite successful.

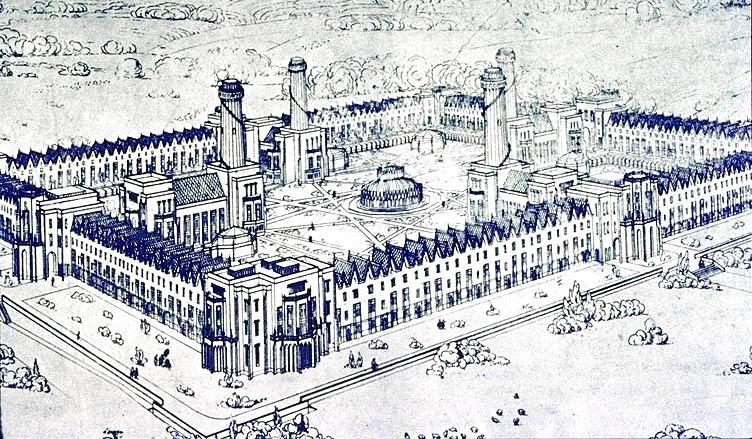

The original Harmonists initially established their first settlement in Pennsylvania, but a rising population and trouble with the locals encouraged them to move westward toward the frontier. A decade later, again perturbed by worldly neighbors, they made plans to return east toward Pittsburgh to settle along the Ohio River, establishing a new community called Economy. The Harmonists sold their land and buildings to Robert Owen for $150,000 in early 1825. He renamed it New Harmony, hoping to establish a model community for social reform and communal living not based on religious beliefs. In a word, instead of the Harmonists’ biblical vision of the Millennium, Owen envisioned a secular paradise on Earth. Owen had been a successful industrialist in New Lanark, Scotland—both as an entrepreneur and in managing an ongoing business. He amassed considerable wealth and was devoted to social progress, putting his principles into practice. For example, at New Lanark he offered housing and education to his workers and their families; he banned corporal punishment in his schools; and he refused to hire child labor under 10 years old.

At New Harmony, Owen looked to extend these principles into a utopian effort at building and maintaining community. For example, New Harmony had the first co-ed public school and one of the nation’s first trade schools. In his 1813 collection of essays, A New View of Society, Owen presented his “science of society”: highly planned communities of 2,000 people with deistic religion (an impersonal Creator God), a focus on reason and rationality, the abolition of private property, and far less emphasis on the nuclear family (Owen 1813).

Owen’s vision attracted many talented people—and thus, New Harmony was initially home to some impressive productivity. In particular, a number of natural scientists settled there—most notably, in geology. His family was especially prolific. Oldest son Robert Dale Owen published the first argument for birth control in America. Separately, as a member of Congress, he also introduced the bill that established the Smithsonian Institutions. Owen’s third son David was responsible for choosing the stone for the Smithsonian building in D.C. and was the first person to be a state geologist in three different states. Youngest son Richard taught at Indiana University and became the first president of Purdue.

Governance in New Harmony was entrusted to a town council of seven—three elected and four appointed by Owen, allowing him to maintain putative control. After a rough and somewhat anarchic start, Owen established a constitution that allowed private property for personal belongings but reserved communal rights for other property while giving residents opportunities to investment in the town’s capital and to work for credit at the town store. A year later, a replacement constitution arranged residents’ duties according to age. However well-intentioned, these efforts and adjustments would not be enough to fulfill the vision because not enough attention was given to motivating production—and the incentives to produce were minimal.

Another likely problem: Owen did not spend much time at New Harmony. As a brand ambassador, he was busy trying to recruit new residents and capital. Owen was effective at getting an audience for his ideas with the most powerful people in American society. He addressed the U.S. Congress and five presidents—in what may have been the first prominent discussions of socialism in America. In 1839, he became one of the first to use the term in print. (Some consider him the father of British socialism.) In other words: although Owen was an eloquent visionary, he didn’t persist in enunciating the vision at New Harmony. Assuming he was reasonably competent as an administrator, his active leadership may have been helpful if not decisive. Instead, the effort quickly floundered without sufficient leadership—or ultimately, sufficient followership.

Owen (and a key partner, William Maclure) heavily subsidized the endeavor at New Harmony. The experiment seemed to have the key variables: smart people, robust idealism, significant resources, a good start, and visionary leadership. But aside from marshaling resources and attracting talented people to follow socialist ideals, it’s difficult to imagine how the structure and incentives of New Harmony’s society and governance deserve any merit. Owen’s vision obscured the hard reality that reallocating wealth and subsidizing production are quite different from motivating the creation of new wealth.

Too little production and disagreement about inequities quickly led to internal strife and then failure, with the dismantling of the project starting in early 1827. Owen sold the property and businesses to various individuals—and in June returned to Europe hoping to find more fertile soil for his ideas and social experiments. People continued to live in New Harmony, but the social experiment phase was over.

The stories at Harmony, New Harmony, and New Lanark—Rogge’s “three morality tales” (Rogge 1979)—hold intriguing similarities but also wild disparities. From Owen’s view, the old Harmony had been run by ignorant and superstitious peasants; his New Harmony was inhabited and run by brilliant men. With the best minds and intentions, what could go wrong? On the surface, old Harmony’s success should have been extended by New Harmony’s infusion of genius and wealth. But by comparison the original Harmony settlement lasted ten years and was prosperous; the New Harmony experiment lasted just two years and was a social and financial disaster.

“Owen’s voluntary work as a compassionate business owner on a small scale was far more effective than his efforts at communal living.”

Rogge’s conclusion: “The Robert Owen who showed the world the way to a better life for all was not the Owen of New Harmony but the Owen of New Lanark, the hardheaded businessman who proved that the humane treatment of others works… it serves the purposes of both employer and employee.” Owen’s voluntary work as a compassionate business owner on a small scale was far more effective than his efforts at communal living. Further along the spectrum, socialism turns out to be much more complicated—ethically and practically—especially on a large scale. As a result, Owen’s legacy, rooted in the textile mills of New Lanark, Scotland, is an ironic testament to freedom, markets, and mutually beneficial trade in business and society.

Christian Socialism?

Communal living (a social system) is a cousin of socialism (a political and economic system). Advocacy of socialism requires faith in government—that politicians and bureaucrats have sufficient knowledge and incentives to run society effectively, and also sufficient morality (e.g., selflessness, integrity) to pursue those ends. Without meeting both criteria, the results will be well-intentioned incompetence (good motives without corresponding good knowledge) or effective corruption (knowledge without motives).

Socialism puts more value on society than the human person. It also requires sufficient drive within followers to work despite its inherent economic disincentives. As such, proponents of government activism in general—and socialism in particular—tend to be a.) confident that ruling elites have good knowledge; b.) ignorant about the need to motivate economic production; c.) naive about human nature including economics trade-offs; and d.) more interested in the welfare of communities than individuals. Owen met all four.

Often, faith in government is explicitly secular but implicitly religious toward the State. For some Christians, their interest in socialism is connected to beliefs on what the Scriptures say about communal living. And then, by way of analogy, socialism has some similarities with the way in which (effective) churches and families routinely function. We’re raised in families, which can be wonderful examples of communal living. And Christians attend churches, which can be impressive examples of shared resources achieving laudable goals. As such, church goers and leaders may be especially prone to believe that socialism can routinely work well—or even, that it is the most desirable form of government.

On the surface, this might appear to be correct. “The people of Israel” and “the Early Church” lived under something of a self-imposed socialistic system. From the Old Testament, Deuteronomy 15:7-9 says: “If there is a poor man among your brothers… be openhanded and freely lend him whatever he needs. Be careful not to harbor this wicked thought: ‘the seventh year, the year for canceling debts, is near’, so that you do not show ill will toward your brother and give him nothing…. Give generously to him and do so without a grudging heart.” While this Scripture speaks primarily of lending, it also implies outright gifts, given the command to retire unpaid debts every seven years. Leviticus 19:10 is even more explicit, while maintaining a work ethic for indigents: “Do not go over your vineyard a second time or pick up the grapes that have fallen. Leave them for the poor and the alien.” From the New Testament’s description of the Early Church, Acts 2:44-45 reports that “all the believers were together and had everything in common. Selling their possessions and goods, they gave to anyone as he had need… ” Acts 4:32-35 is similar: “All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of his possessions was his own, but they shared everything they had…. There were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned lands or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone as he had need.” This sounds similar to Karl Marx’ dictum: “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” In a word, the Early Church lived out socialism of a type: all income and wealth went into a common pool to be distributed by their leaders as necessary. Acts 2:47 reports that “the Lord added to their number daily those who were being saved.” Clearly, God was happy with this system. It is easy to understand why some have interpreted these verses as calling on believers to put faith in governments to redistribute wealth and uphold socialism as a national economic system.

But there are two key differences between the Biblical call for individual Christians and what the Bible has to say about the optimal role of government. First, Israel and the Early Church are examples of relatively voluntary behavior. In stark contrast, government activity is coercive. (While the dictates of biblical community might be enforced within the group, people always have the option to leave.) Second, Israelite society and the Early Church were governed at local levels and on relatively smaller scales where socialism tends to be more effective. Government activity is often non-local and conducted on a large scale—both of which introduce an array of knowledge and incentive problems. With any form of wealth redistribution based on need, there are incentive problems for recipients—those in need. Textbook issues including the free rider problem and Prisoners’ Dilemmas are exacerbated when moving away from local and small scale to more writ large arrangements. For instance, it is easier to discern true need and monitor the behavior of recipients in a smaller local setting; fraud and long-term dependency are less likely. Further, to the extent that guilt is a factor, people are more likely to abuse a system run by a distant and impersonal government rather than people in their own communities. This is not to say all people will reduce effort in large-scale settings. But at the margin, shirking becomes more likely for each individual. Certainly, there are those who will work despite receiving little directly from the fruits of their labor. Historically, the Early Church, various communes, and Israeli kibbutzes have largely avoided shirking. But these people are driven by something in addition to economic incentives—a devotion to religious teachings and a form of work ethic.

Objective standards for productivity allow for easier monitoring. And of course, having intrinsically motivated people can be quite helpful. When I’m teaching economics for business students, we frequently talk about incentives in the workplace. This leads to the takeaway that collective arrangements work better and easier when people are internally driven to “do the right thing”, underlining the crucial importance of the Humna Resources function in firms.

About 1,000 people joined the experiment at New Harmony. Owen cast a wide net in his invitation to join the community. Not surprisingly, he attracted a mixture of true believers, eccentrics, and free riders. One of his sons described the residents as “a heterogeneous collection of radicals, enthusiastic devotees to principle, honest latitudinarians, and lazy theorists, with a sprinkling of unprincipled sharpers thrown in.” More homogeneity in participants allows them to be “on the same page”—as well as to monitor and enforce standards with people they understand better. Because Owen was hostile to “organized religion”, his community may have had more homogeneity in this regard. The bad news is that he reduced or eliminated a helpful motive for people who might have been called to be productive for higher purposes. If Owen had been more selective, success would have been more likely. But in the end, the diligent grew to resent those who responded to the incentives at hand.

Even in special cases where communal living has been relatively effective, incentive problems are still present. Again, the example of the Early Church is instructive. Acts 5 relates the story of Ananias and Sapphira, a married couple who voluntarily sold a piece of property and claimed to give the entire proceeds to the church. Instead, they kept part of the money for themselves. By lying to the leaders, they responded to the economic disincentives at the expense of their supposed moral beliefs.

The same tension is evident throughout Paul’s letters to churches. He frequently encourages work, condemns laziness, and discourages financial dependency on others. He was teaching against the incentive problems inherent in any socialistic system. Implicitly, he was encouraging an increase in monitoring and discipline to stem the tendency to “free ride” against the efforts of others.

Other lessons

By two metrics, Owen clearly deserves immense credit. First, in business and in his efforts at social reform, he put his money where his mouth was. He was willing to sacrifice profit to do business by his principles and he devoted much of his wealth to his ideals for communal living. Second, his vision was based on charity from philanthropists and cooperation from community members, rather than advocating socialism per se or agitating the working classes to rebel and establish it by force.

Too often, people conflate their personal convictions with a need to press those convictions on others, especially through the use of government’s coercive powers. This is a mistake. Even if something is a good idea, it doesn’t follow that government is an ethical and practical means to the desired ends, forcing conformity to those beliefs. Owen didn’t commit this particular mistake and instead relied on voluntary behavior—both for financing these communities and, largely, in governing them.

In this way, Rogge’s three moralities mirrors some of the most classic economic arguments against socialism. In their 2019 book, Socialism Sucks: Two Economists Drink Their Way Through the Unfree World, Robert Lawson and Benjamin Powell offer a breezy take on socialism (Lawson and Powell 2019). Its casual tone is rooted in their use of beer as a metaphor and a key prop to describe different types of socialism in various countries. Lawson and Powell’s punchline: many people advocate socialism without knowing what it is. (Not many people understand capitalism either, but that’s another story.) Socialism is defined as government owning all means of production. But few people really want that, including most self-styled socialists. Instead, they imagine “socialism” as a dog’s breakfast of leftist and liberal policy proposals. They see it as a vague call to increase government activism, justice, and ironically, “democracy.”

For more on these topics, see

So, for readers worried about people advocating (real) socialism today, you can rest easy. They’re not advocating political oppression and the abolition of private property. They’re usually fans of watered-down versions of socialism: government interventions fraught with inefficiencies, inequities, and a mix of good intentions, cronyism, and ignorance of economics and/or Scripture. Although the ideas may look good on paper, they rarely work out, either ethically or practically. In this, naive utopians such as Robert Owen are actually fine examples. The world would be a far better place if socialist wannabes considered how their good intentions might be better achieved through voluntary efforts in business, politics, and society.

References

Lawson, R. and B. Powell. 2019. Socialism Sucks: Two Economists Drink Their Way Through the Unfree World. Regnery.

Owen, R. (1813). A New View of Society.

Schansberg, D. (1996). Poor Policy: How Government Harms the Poor. Westview.

Footnotes

[1] Available online at the Library of Economics and Liberty: “Paradise in Posey County,” in Can Capitalism Survive? by Benjamin Rogge.

[2] I develop this case in greater detail in Schansberg (1996).

*D. Eric Schansberg is Professor of Economics at Indiana University Southeast and the author of Turn Neither to the Right nor to the Left: A Thinking Christian’s Guide to Politics and Public Policy.

This article was edited by Features Editor Ed Lopez.