Many years ago, shortly after joining the Marines, I signed up for a bone marrow donor registry. I had mostly forgotten about this as the years passed until one day in June 2020, I received a call from my father. He had received a call from the clerk’s office. (When I first registered, I didn’t have a cell phone of my own, so I simply wrote down my old home phone number as my contact information.) It turned out that I was an ideal match for someone suffering from leukemia and in need of a bone marrow transplant. My father passed on the information he gathered to me, and I contacted the registry office.

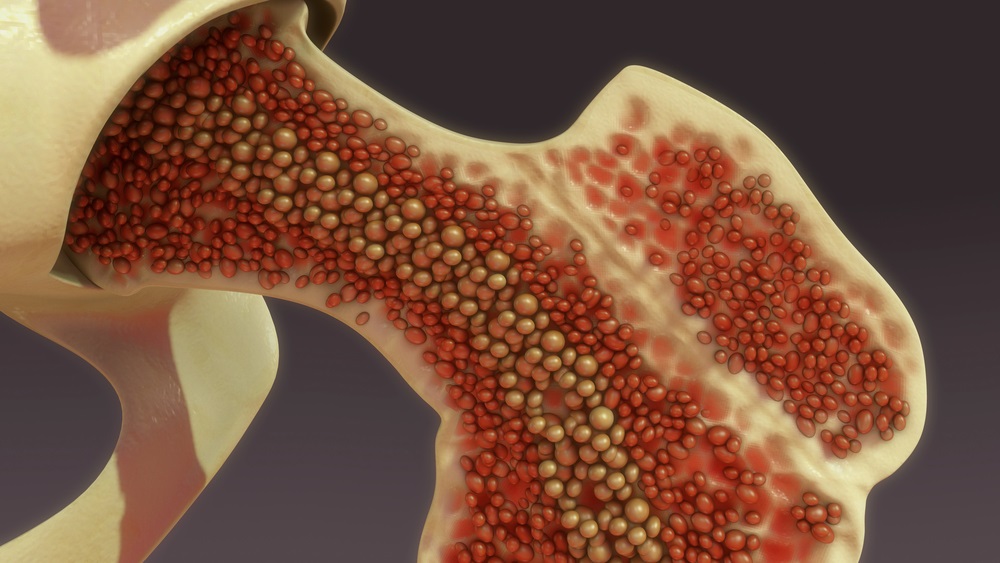

My only idea of how bone marrow transplantation worked came from what I remembered from medical shows – which usually involved inserting a giant needle into the bone to extract marrow. This turned out to require a different method. A few days prior to the donation, a nurse came to my house daily to administer filgrastim injections. This, in turn, would cause my body to overproduce bone marrow stem cells, which would enter my bloodstream. I was also told that common side effects of filgrastim injections included significant muscle, joint, and bone pain, along with headaches, weakness, and nausea. After a week of these injections, I spent several hours hooked up to what was essentially a dialysis machine that would filter these cells from my bloodstream and make them available to the person in need.

That all sounded like a lot to go through. Adding to the complications, this was June 2020 – still the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. I was already cautious about the disease because I feared that my history as a heavy smoker might have made me more vulnerable to respiratory disease. Taking extra risks seemed, well, risky. Adding to the complication, my wife and I had welcomed our firstborn into the world in mid-May 2020, just a few weeks earlier. As any parent can attest, we hadn’t slept more than a few hours at a time since then. Spending a week experiencing the side effects of these injections, while also being able to do my job and care for a newborn, seemed very intimidating.

Ultimately, I decided I was going to go ahead and do it. I was already feeling pretty ragged and it would end up being a difficult time leading up to the donation, plus the unpleasantness that comes with the donation process. But I wasn’t die – and someone else was, and I could help save them. I’m glad I did. But at that moment I was on the same page with my decision. If I had been a little more cautious about Covid and possible complications, a little more exhausted by the newborn phase, a little more concerned about the painful side effects of the injections – I could very well have ended up on the other end of the line.

This phase where we are right on the border, right at the tipping point of the transition from one option to an alternative, is what economists have in mind when we talk about ‘the margin’. When I made that decision, I was the marginal donor—the person who was just on the cusp of being willing to go through with it. The costs were all the complications described above, the benefits were the fulfillment of a general desire to help someone in need. For me, the benefits just outweighed the costs at that moment. But suppose that wasn’t the case. Suppose that my general desire to help people was somewhat lower, or that I had weighed (some of) those costs more heavily at the time. In that case I would hardly have been in the market other side of the line. Almost willing to donate, but not quite. Do you know what would have made a difference in those cases and tipped the balance towards donation? The prospect of getting paid.

If my willingness to donate had just fallen short, just a small payment offered would have been enough to push me over the donation line. If my reservations had been stronger, a larger payment would have been required. And so on.

In the United States, it is against the law to be paid for donating an organ. Everyone else involved in the procedure – the hospital and medical staff, for example – can be paid for their part in a kidney transplant, for example, but if the person actually losing a kidney receives any compensation for their part in the process, then it is a crime. As a result, kidneys can only be given by donors who are willing to do so for free. The number of such people is not zero – Scott Alexander is such a person – but the number is demonstrably much, much lower than the number of kidneys sick people need. This is why there is a huge backlog waiting for a donor kidney, with thousands of them dying every year before a donor can be found.

The number of people with a Scott-Alexander level of altruism is not enough. But what about people who are on the edge of the line? People who are almost, but not quite, altruistic enough to donate a kidney for free. For these people, only a small amount of compensation would be needed to take them across the line from not quite willing to donate to willing to donate. And when those people cross the line, there will be a new wave of people who are just on the side of this new line. People whose altruism is combined with a small compensation almost But not quite enough to make them willing to donate. If, after a small compensation, there are still more people in need of kidneys than there are willing donors, the price can go up and just win over this next group of people. This process could continue until the price is so high that the last person needed crosses the line from “not quite willing” to “barely willing” – that is, the final price for donor kidneys will ultimately be set at the margin. .

According to this website, in September 2024, approximately ninety thousand people in the United States were waiting for a kidney transplant. About a dozen of them will die every day while they wait. Last year, a total of approximately 27,000 kidney transplants took place. That is a shortage of more than 60,000 kidneys. The question is: how high should the price be to move 60,000 people from barely willing to donate to being willing? It may be lower than you suspect. Even if most people wouldn’t consider donating a kidney for less than a million dollars, prices aren’t determined by what most people want. Prices have been fixed at the margin. This would only require the payment to be high enough to motivate the 60,000 people who are already most likely to donate, starting with those who do. only just now unwilling to donate for free. I wouldn’t be surprised if the payment needed to fill the gap turns out to be quite small.

Many people don’t like the idea of paid organ donation. Debra Satz raises a number of objections to the idea in her book Why some things shouldn’t be for sale: the moral limits of markets. It’s an excellent book. But none of the arguments are even remotely powerful enough to overcome the simple fact that today a dozen people will die waiting for a kidney. Another dozen tomorrow, and the day after that, and at Christmas, and… every other day until we get more kidneys. In contrast, all of Satz’s concerns about “abhorrent transactions” are just a storm in a teacup.