A study published Thursday provides sobering news about the H5N1 bird flu viruses circulating in cows in the United States: A single mutation in the hemagglutinin, the key protein on the outside of H5N1, could change a virus that is currently ill-equipped to infect. to convert people into an organization that is much better able to do this.

Scientists from Scripps Research in La Jolla, California, reported in the journal Science that one mutation in the hemagglutinin changed the type of cell receptors to which the virus is best suited to attach, changing its preference from those of birds to those of the human upper respiratory tract.

The authors called their finding “a clear concern” — a view shared by other flu scientists asked by STAT to review the paper. Debby van Riel, a virologist at the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, Netherlands, suggested it could be that the version of the virus currently spreading among cows has higher zoonotic potential – a greater ability to jump species – than previous ones versions of H5N1. But she and others, including the Scripps team itself, warned that this one change alone might not be enough to turn this virus into an efficient human pathogen.

While “the mutation to recognize human-type receptors is a critical step, additional mutations are likely required to make the virus fully transmissible between humans,” said Yoshihiro Kawaoka, a cross-appointed influenza virologist at the University of Wisconsin- Madison and the University of Tokyo, STAT told in an email. “Unfortunately, we don’t yet know what these additional mutations might be because this area of research has not yet been extensively studied.”

Adding to the concern is the fact that a mutation at the same position on the hemagglutinin that the group studied recently saw in viruses taken from a teenager in British Columbia, Canada, who contracted H5N1 in late October and became seriously ill. The teenager has been in critical condition in a Vancouver hospital for several weeks. Authorities there could not determine how the teenager became infected.

The mutation in the Canadian teen was at a position known as 226 on the receptor binding site of hemagglutinin – the position that the Scripps team said was critical for changing the receptor binding preference. But the amino acid changes in the teen virus were not identical to the changes that the Scripps team had shown changed the receptor binding preference. The mutation at position 226 was one of two major hemagglutinin changes observed in the teenager’s virus.

It is not known whether the mutation was in the virus that first infected the teen, or whether the mutation developed in the teen during the infection – although scientists suspect the latter. However, it appears that the teenager – who is no longer contagious – did not pass the virus on to anyone else, so the mutated virus will have died out.

Scott Hensley, a professor of microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, described the finding that a single mutation could change the receptor binding preference of this version of H5N1 as “alarming” – especially in light of the Canadian case.

“I think there is a chance – I’m not saying there is a chance [have] happened, but I think there is a chance that these two replacements in the British Columbia case could have caused a pandemic if enough people had been exposed to that virus,” Hensley said.

It has long been assumed that H5N1 or any avian flu virus would need to change its receptor binding preference to acquire the ability to spread easily among humans – a development that would cause a pandemic. This type of binding switch was observed in the flu pandemics of 1918, 1957, 1968 and 2009. But research by the Scripps team on earlier versions of H5N1 suggested that multiple mutations would be needed to achieve this goal.

This time was different.

“It was quite difficult to change the receptor specificity of H5N1 viruses before,” Ian Wilson, one of the paper’s two senior authors, said in an interview. But when the group studied the hemagglutinin of a virus recovered from the first confirmed human case in this outbreak, a dairy farmer in Texas, “to our surprise, the single mutation… could actually change that receptor specificity.”

Wilson, a professor of structural biology at Scripps, called the fact that a mutation at the same position in the virus appeared in the British Columbia teen “remarkable.”

The fact that three or more mutations were previously required to change the virus’s receptor binding preference set the bar high for scaling up the virus. However, one mutation changes the calculus, the article noted. “Because each mutation is independent and the probability of achieving additional mutations decreases exponentially, our observation that a single mutation is sufficient to alter receptor specificity…dramatically increases the probability of achieving this phenotype required for human transmission,” the authors wrote.

That said, Wilson emphasized that the team did not want to overemphasize their findings, as their research cannot predict whether the virus will make this change, or if this is the only way a change in receptor binding preference could occur.

“It’s clear that H5N1 infections have been around for a long time, but that hasn’t happened yet,” he said. “However, this virus is a little different.”

Research by Van Riel and colleagues from Erasmus supports this idea. In a recent preprint (a paper that has not yet undergone peer review), they reported that a 2022 version of the virus – from the same subset or clade as the virus now circulating in cows – attached more easily to human respiratory cells than an H5N1 virus that circulated in 2005.

This version of the virus is known as clade 2.3.4.4b. So far this year, 58 people in the United States have been infected with this virus. (The teenager in British Columbia was also infected with a 2.3.4.4b virus, although that was slightly different from the virus circulating in cows.) Most cases in the US have occurred on affected dairy farms or have been involved in culling infected poultry. . No one has had a serious illness – a fact Hensley worries has led the agricultural sector to dismiss the threat posed by the virus.

Farmers in many parts of the country have resisted testing for the virus, and there is widespread belief that more farms and more states have had outbreaks than they have reported. On Thursday, the U.S. Department of Agriculture confirmed 718 herds in 15 states since the outbreak was first discovered in late March.

“There is a general idea among farmers and people in government that this is not the case [a big deal] – why do anything?” Hensley said. “As we saw in the British Columbia case, a single substitution or two or three substitutions can completely change that equation. And suddenly you can get a virus that is much more pathogenic.”

Seema Lakdawala, associate professor in the department of microbiology and immunology at Emory University School of Medicine, agrees.

“We as a country do not take H5 seriously enough. Absolute. This article does nothing to remind me anymore [of that]” said Lakdawala. “But if it reminds others that it’s important, that’s fine.”

She and others STAT spoke to about the study described the work as very good science.

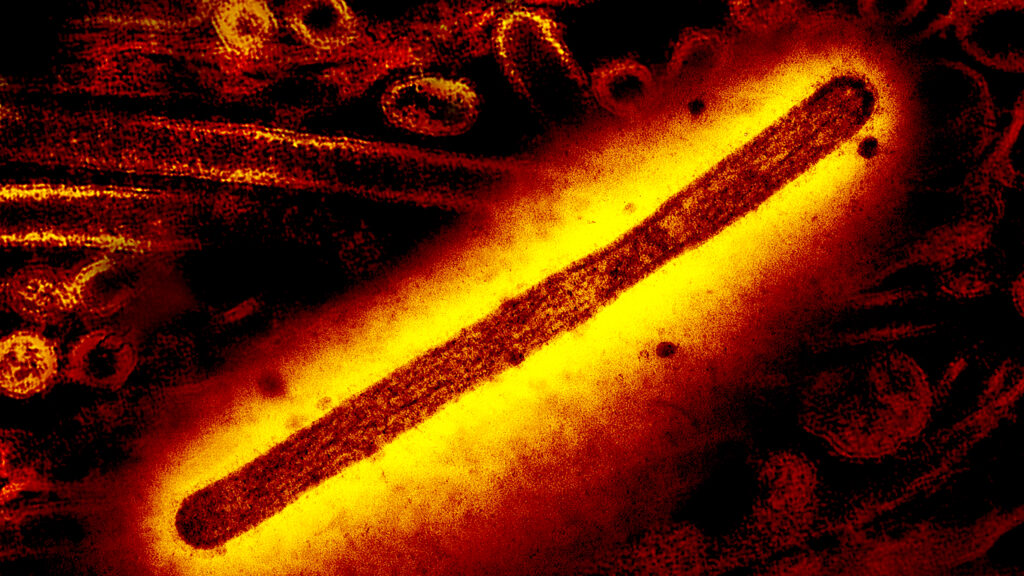

The Scripps team wanted to see what it would take to give the hemagglutinin protein of this version of the virus the ability to easily attach to cells in the human respiratory tract. So it looked at what might happen if mutations occurred at sites on the protein known to change the receptors to which the virus can attach.

Bird flu viruses attach to receptors known as alpha 2-3, which are abundant in birds but rare in the upper respiratory tract of humans. In humans, alpha 2-3 receptors are found primarily in the mucous membrane around the eyes – most human cases in the US have suffered from eye infections – and deep in the lungs. In the upper respiratory tract of humans, a type of receptor known as alpha 2-6 predominates. The mutation the Scripps team identified changed the binding preference from alpha 2-3 to alpha 2-6 receptors.

The work was done by studying the hemagglutinin of a virus that infected the first confirmed human case in the US this year, a farm worker in Texas who was believed to have been infected through exposure to infected cows.

The team did not work with whole living viruses. Adding mutations to avian flu viruses that could increase their ability to infect humans is considered a “gain of function” or boosting potential research into pandemic pathogens. This type of work cannot be conducted in the United States with federal research funding without prior approval from the National Institutes of Health.

Ron Fouchier, a virologist at the Erasmus Medical Center who has been studying H5N1 for more than two decades, suggested that the Scripps article should serve as a reminder of why it is dangerous to allow H5N1 to circulate unchecked in cows.

“The manuscript … demonstrates that the US H5 influenza viruses from cows can readily acquire human receptor specificity, providing another reason for the rapid eradication of this virus from the US cow population,” he said in an email.

Lakdawala agreed. “Every single case, every single spillover has the potential to adapt,” she said.