bCancer surgeons tend not to force patients to undergo bilateral mastectomy because data has long shown that complete removal of both breasts does not improve survival. New data from a large epidemiological study confirms that, but an accompanying finding is confusing. Breast cancer survivors who eventually developed a second breast cancer in the opposite or contralateral breast had a higher risk of death, even though preventing the cancer with surgery did not change the outcome.

“That seems like a paradox,” says Steven Narod, a breast cancer researcher and physician at Women’s College Hospital in Toronto and lead author of the study. “If you get contralateral breast cancer, your risk of death increases. But preventing it does not improve your survival.”

Still, he and other experts said the data should not change the decision calculus around whether to opt for a bilateral mastectomy or a less intensive procedure. Rather, he said, the study raises important scientific questions about contralateral breast cancers and how breast cancer metastasizes and kills.

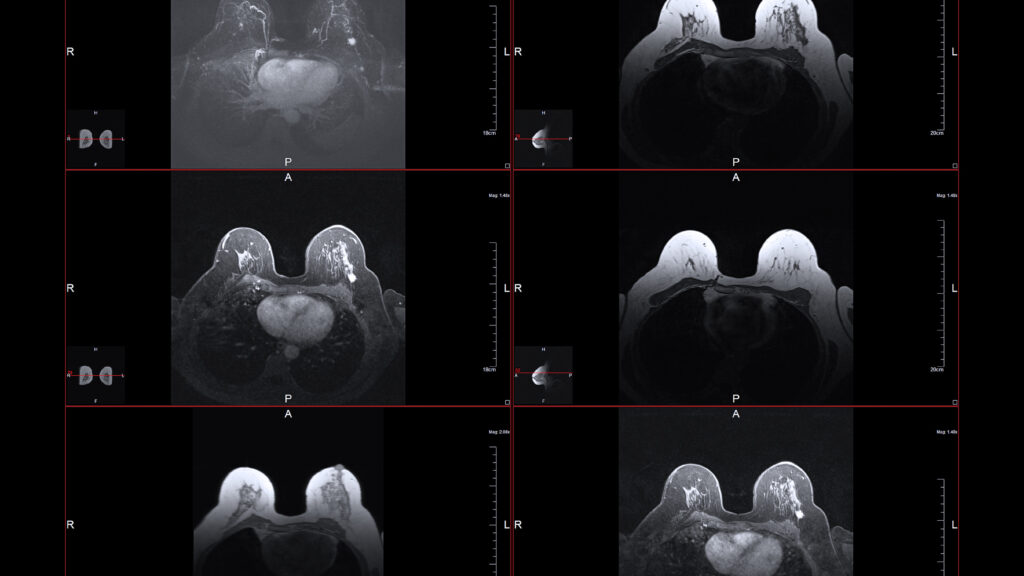

To conduct the study, Narod and his colleagues compared data from 100,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer between 2000 and 2019 and given one of three surgical options. All breast cancer patients who undergo surgery choose between a lumpectomy, a simpler procedure that removes only the tumor and some of the surrounding tissue, a single or unilateral mastectomy that removes only the affected breast, or a bilateral or double mastectomy. The point of the unilateral mastectomy is that it can prevent the return of the cancer in the same breast or an ipsilateral recurrence. Likewise, bilateral mastectomy prevents cancer from recurring in both breasts. Without this, contralateral breast cancer occurs about 7% of the time.

In the analysis, published on Thursday in JAMA Oncologythere was no significant difference in survival between all three groups. More than 80% of women did not die from breast cancer after twenty years of follow-up, regardless of which surgery they underwent. At the same time, the article also showed that women who later developed breast cancer in the other breast had a fourfold higher risk of death. Therein lies the mystery, Narod said. It is still not entirely clear what is responsible for this result.

One thought is that the situation might be similar to asking why survival does not differ between having a lumpectomy and a single mastectomy, even though recurrence in the same breast is associated with worse outcomes. This is mainly because mastectomy did not reduce the risk of metastatic recurrence. In this case, the local recurrence may be a sign that something has gone wrong with the initial tumor, such as an early indication that the initial treatment has failed and microscopic metastases have been left behind. “A signal that something is going on systemically,” Narod said. “That the lungs, liver, brain and bones can also be affected.”

That could also indicate that the contralateral breast cancer is a metastasis from the first breast cancer, Narod added.

However, a potential problem with this explanation is that a significant proportion of women diagnosed with contralateral breast cancer developed it at an advanced stage, when the disease was already incurable. “I don’t think it works in this situation because of the phase shift,” says Seema Khan, a breast surgeon at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, who wrote an accompanying letter. editorial in JAMA oncology, but did not work on the study. “Some of the greater danger comes from the fact that the stages in the second event were worse.”

Possibly, Khan added, the increased risk of death among those who developed contralateral breast cancer is an “artifact finding” caused by an as-yet-undetermined error in the experimental technique or data. Although, she added, this isn’t the first time a study has found that contralateral breast cancer can lead to worse outcomes. A Swedish study in 2007 reported women who developed cancer in the second breast within five years of their initial breast cancer diagnosis were more likely to die, while women who developed the contralateral breast cancer more than ten years after their initial diagnosis did not.

Another idea is that the appearance of a second tumor could trigger more aggressive behavior in malignant cells that spread throughout the body from the first tumor, said Julio Aguirre-Ghiso, a cancer researcher at Albert Einstein College of Medicine who did not participate in the study. cooperated. . “At stage 0, there may already be proliferation of cells that can cause metastasis,” he said.

What might happen is that after the initial cancer is treated, these early, distantly spread cells “go dormant.” Sitting there. If nothing happens, they are unlikely to metastasize,” Aguirre-Ghiso said. But it is possible that if a second tumor develops, such as in the other breast, and that tumor spreads its own cells throughout the body, this could accelerate the formation of metastases that would always arise from the first cancer anyway.

That could help explain why it appears that the risk of death is higher in people who develop contralateral breast cancer, even though those who had a double mastectomy still died at similar rates. Preventing contralateral breast cancer prevents cancer from developing in the other breast, but not from spreading elsewhere in the body.

But that idea, like the others, will still require a lot of research to support. The benefit of this could be finding better ways to prevent metastatic recurrence in breast cancer survivors, Aguirre-Ghiso said.

For breast cancer patients trying to choose which surgery to have, the factors still haven’t changed, said Laura Esserman, a breast surgeon and cancer researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, who did not work on the study. Many patients still decide to undergo the more serious double mastectomy for reasons such as anxiety relief, reducing the discomfort of breast cancer surveillance, or carrying mutations such as BRCA 1 that increase cancer risk. Those can be sensible reasons, Esserman said, as long as people are properly informed that the procedure won’t change their chances of survival.

“I’m a big believer in giving people advance advice before surgery,” she said. “I try to give people time to think about it.”