Table of Contents

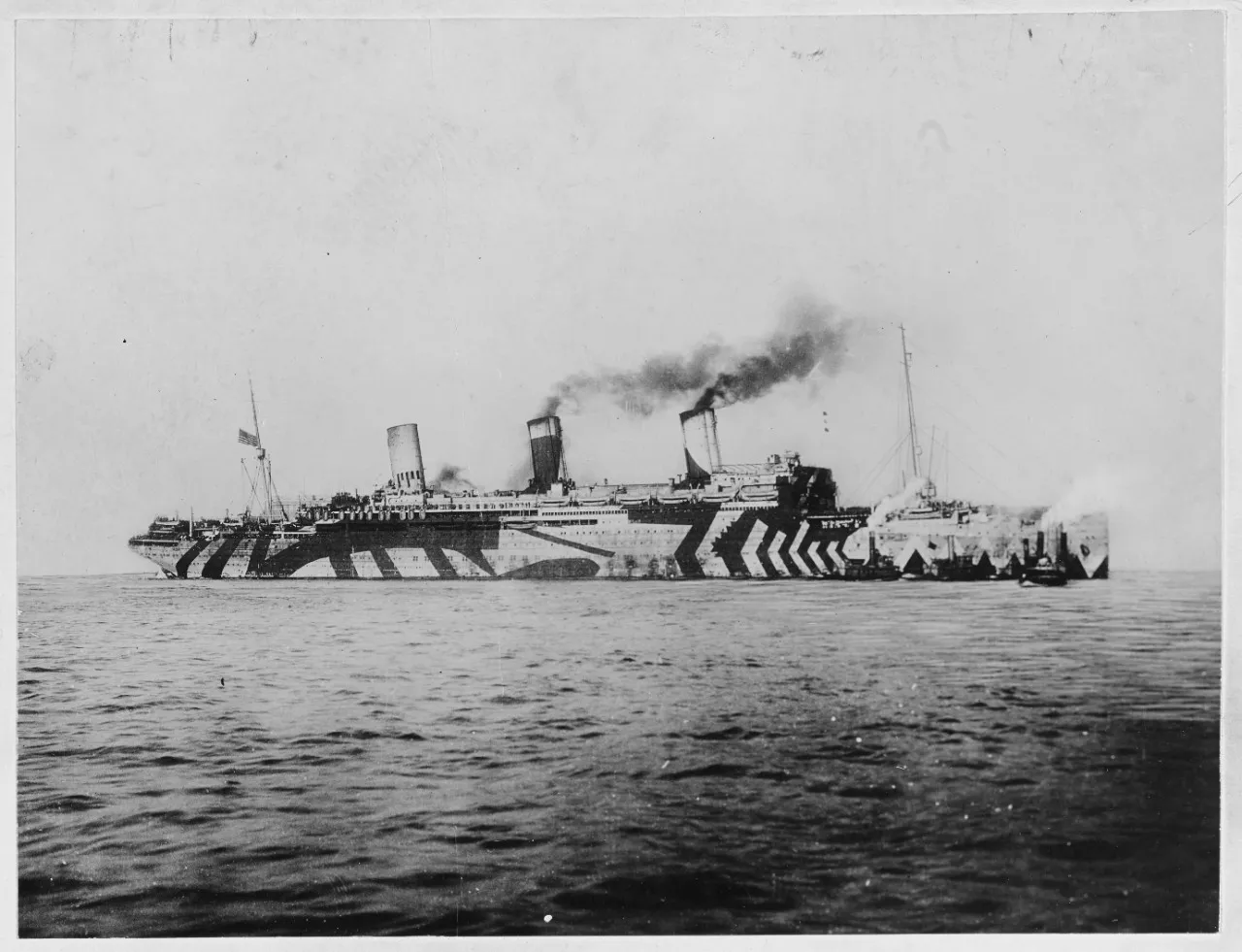

During the First World War, Allied Marines began to implement shocking, cubic “Dazzle” paint lanes on ships. The now iconic geometric designs were intended to throw off the visual perception of German U-Boats crews and to prevent them from gathering on ships with torpedoes. Conventional wisdom claims that the bizarre camouflage pattern worked and helped to turn the tide of Great War Naval Battles. But new research that one of the few rigorous studies again evaluates that testing that hypothesis suggests that those conclusions were probably exaggerated. Researchers now claim that a different phenomena known as the “horizone effect” may have done more to throw submarine -canon goers than crazy aesthetics.

The study, published last week by researchers from Aston University in the diary I perceptionHas one of the few solid quantitative studies into the effectiveness of ship, where the methods are updated to meet modern scientific standards. The revised findings claim that the original study “overestimates the effectiveness of the camouflage of blinding dazzling.” Although the modernist designs may have played a role in deforming the perception of the movement and the direction of a ship movement, the new study also found similar effects to ships painted in standard, single-color palettes. According to the researchers, U-Boat Gunners who looked at ships from a distance probably fell for an optical illusion that makes the ships seem to look like they were traveling along the horizon. That illusion probably occurred whether the ships were “blinded” or not.

“These re -assessed findings solve a clear conflict with the second quantitative experiment about blinding ships that are performed more than a century later using computer displays online,” researchers write.

Dazzle: a different kind of ‘camouflage’

The Dazzle Paint scheme was created around 1917 as a direct response to unexpected German U-boat attacks. German ships took an “unlimited submarine war” policy at the beginning of the year that He reportedly resulted in hundreds of sunken shipsBoth military and trader, in less than a year. One of those down boats, a British hospital vessel called the HMHS Lanfranc Reportedly resulted in 40 deaths. Looking for a solution, the English artist Norman Wilkinson approached the British king George V With models of ships decorated in zigzag and checkered patterns in shades of gray, black, white, green, orange and blue. Wilkinson claimed that these strange forms, which were viewed from a distance by a U-boat periscope, would distort the appearance of the ship just enough to make it difficult for submarine operators to follow them accurately and to focus with torpedoes. Convinced by the demonstration, King George approved the implementation of blinding designs in the British fleet.

Wilkinson’s blinding approach followed on the heels of other, less practical proposals. Shipmakers were reportedly attempted at different times to kill and paint ships in mirrors Looking like gigantic clouds and whales. The American inventor Thomas Edison has reportedly even brought forward an idea to re -configure ships Looks like floating islands lush with foliage. All these ideas finally failed because they could not explain the constantly changing environments and weather conditions at sea. It was simply not possible to fully camouflage a ship in a way that consistently mixed in its environment. Dazzle has chosen a completely different approach. Instead of trying to disappear, the unorthodox geometric shapes were aimed at confusing the perception of an observer of the movement and orientation of a ship remotely.

Did Dazzle really work? New research makes doubt.

Although widely adopted by both British and American ships during the war, Dazzle Camouflage was usually implemented on the basis of assumption instead of solid evidence. Limited, high -quality empirical research from the time that was actually measured, regardless of whether the Dazzle worked as advertised. One of the few remaining quantitative studies into its effectiveness was carried out in 1919 by a MIT marine architecture and student Marine Engineering called Leo Blodgett as part of his thesis.

In the study painted Blodgett model painted with blinding patterns and placed them in a false slag theater. He then observed them remotely through a periscope and claimed that the blinding effect confused the perception of the observer of the movement of the ships. But when the researchers from Aston University looked back on the findings, they found several holes in the study, especially in the Blodgett control group, which do not measure modern standards. According to researcher and co-author Samantha Strong, those shortcomings made in the control experiment, Blodgett’s experiment made too vague to be useful “. The Aston researchers went back in and created a new control experiment based on processed images of the original results. The newly improved methods showed the optical illusions that took place in cases where the ships had and did not have the blinding paint.

“We have carried out our own version of the experiment using photos from his thesis and compared the results in the original Dazzle Camouflage versions and versions with the camouflage edited,” Strong said. “Our experiment worked well. Both types of ships produced the horizone effect, but the glare imposed an extra turn.”

If the first findings of Blodgett were to be kept, the researchers noted, the front (or bow) of the ship would seem to run consistently from the direction in which it actually drove. In reality, the researchers found various cases in which the observer again observed the bow of the ship, even while it left. This illusion, she claims, probably had more to do with the “horizone effect” – a phenomenon in which a ship seems to travel along the horizon, regardless of the actual direction – than with the dazzling camouflage itself. The researchers also noted that ships travel up to 25 degrees in relation to a horizon will still look like they are traveling with it from the observer’s point of view.

“The remarkable finding here is that the same two effects, in similar proportions, are clearly clear in participants who are familiar with the art of camouflage disement, including a lieutenant at a European Navy”, Aston University Professor and paper co-author Tim Meese said in a statement.

Unveiling as the findings are, she does not necessarily mean that Dazzle was completely not effective. As noted in a 2016 Smithsonian reportMailing shipping ships dressed with the blinding pattern during the war are reportedly granted lower insurance premiums. Some captains of the ship at that time also claimed that the moral of the crew looked higher on ships with the blinding pattern than those without. Even if the actual illusory effect of the glare was minimal, people bought the hype and believed It was effective.

In other words, never count the placebo effect, even in times of war.